Selling Women the Green Dream: Femwashing, Ultra Fast-Fashion and the Radical Act of Slowing Down

Recently we sat down with the author of research paper, ‘Selling Women the Green Dream’, Mariko Takedomi Karlssona (co-authored by Dr. Vasna Ramasar) to discuss why advertising techniques such as greenwashing and femwashing are gaining momentum and what we as consumers can do to disrupt this trend.

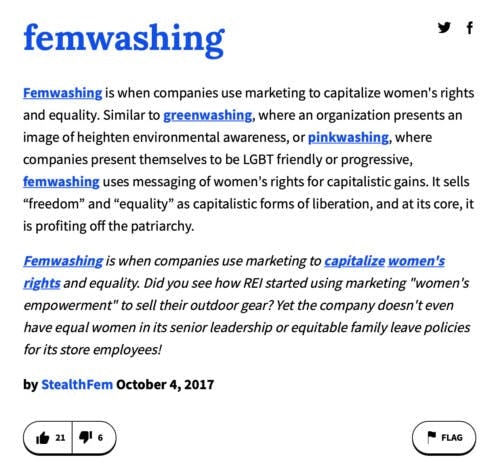

Georgia Taylor-Stidwell: What would you define as ‘femwashing’?

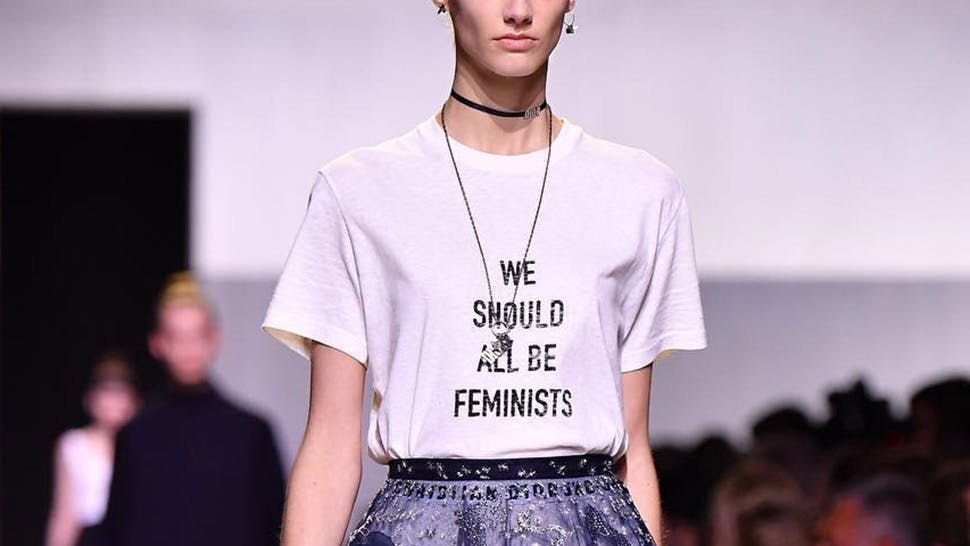

Mariko Takedomi Karlssona: To me femwashing or femvertising is when companies communicate through advertisement that the consumption of their products is somehow going to lead to gender equality or female empowerment or that their products are somehow feminist.

I do not know if I have seen any clear changes in this marketing trend yet. If anything, I have seen a growth in this type of advertisement, more and more companies are using greenwashing and femwashing techniques. I think companies are getting more skilled at doing this in a very subtle and very effective way.

GTS: Why specifically are women the target of ‘greenwashing’ and ‘femwashing’ campaigns?

MTK: My argument in my research is that this is based on traditional ideas of femininity and the role of women. It is based on this dichotomy between masculinity and femininity, especially prevalent in Western societies where women have been associated with nature and emotion and men have been associated with culture, science and rationality.

This is one of the reasons women are still seen as more nurturing and caring for the environment. We place a lot of environmental responsibility on women globally. Women have typically been associated with consumption and men have been associated with production, I think that has led to women being the gatekeepers of the family unit in terms of what is purchased for the household.

In terms of greenwashing and sustainable products, researchers have shown how household products and baby products have been advertised to women. It has been seen as the mother’s role to be the protector of the family and the household and the femwashing trend within fashion advertisements is a development of this.

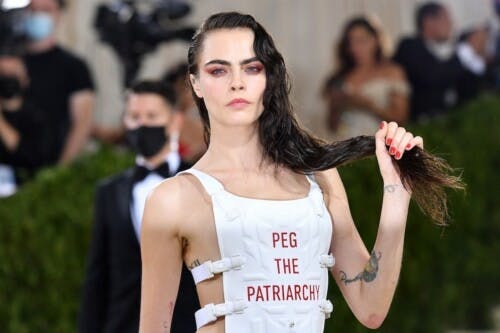

Cara Delevingne at the 2021 Met Gala

GTS: Is there anything we as consumers can do to push past this ‘at least we are doing something’ mentality when indulging in ‘femwashed’ or ‘greenwashed’ products?

MTK: There are a lot of things we can do as consumers, one of them is to try to examine why we feel the need to buy certain things and to be critical of this kind of addictive urge to refashion ourselves and redefine ourselves constantly and at a really fast pace. It is important to try to think deeply about when we feel the need to buy something or change ourselves through the act of consumption. We can ask ourselves ‘is this really going to change my life or make me a better person?’

It sounds cheesy but the industry of fast fashion is reliant on the addictive fast pace of consumption. Things like mindfulness and taking a step back and letting things be slow can be a good antidote. We need to slow down to realise we don’t need all these things. Do we really need to keep up with this pace of having new things all the time? Perhaps there are other ways of living that can be more satisfactory and that could maybe lead to us not feeling the need to fill any void through consumption.

GTS: Have you witnessed any progress in the breakdown of alienation between consumer and producer in recent years?

One of the things I have been thinking about lately is these new fashion companies that are even faster than fast fashion, some people have been calling them ‘ultra fast fashion’, like Shein for example. They have removed the entire retail aspect of the value chain so it is just a website, factory and straight to the consumer and almost all advertising is done through social media.

I think one of the really interesting things about this is that because the timeline has become so compressed. From seeing a celebrity wear something, to Shein producing an exact copy of it, to seeing an influencer wearing it, to being able to wear it, it has shrunk to the point that it can have an effect in terms of alienation. It creates an even larger distance between the consumer and understanding what this product is and what it means in terms of embodied labour.

GTS: Do you have any advice for those trying to see through ‘femwashing’ and ‘greenwashing’ tactics?

We can try to be alert, try to examine ourselves and our emotional needs when it comes to buying things, ask ourselves: is this about something else and is the act of consumption really going to make that better?

If something is advertised as if you buy this you are helping a cause, either female empowerment or the environment, a useful exercise would be to ask ourselves: is there something else i could do that would actually help this cause that does not involve me buying something? Can I help by becoming involved in a community activity? Is there something closer to myself that I can help with?

Click here to read Mariko Takedomi Karlssona and Dr. Vasna Ramasar’s research article in full